Museum der Kulturen

Basel

Münsterplatz

20, 4051 Basel, Basel-Stadt

Text by Lucia Messer

How

to decolonize a museum

The Museum

of Cultures Basel (MKB) is the biggest ethnographical museum of Switzerland and

holds a collection of over 340’000 objects from around the world. It aims to

“shed light on the cultural dimensions of life that define each and every

society in multiple and different ways” (MKB n.d. a). To decolonize a museum's

narratives and the collection they are based on, it is worth looking at the

context of acquisition and the provenance of its objects as they hold the power

to spark new discussions and change. This might be especially true for

Switzerland as some of the objects tell stories about colonial entanglements,

which Switzerland prefers to deny or hide.

Figure 1 Museum der Kulturen

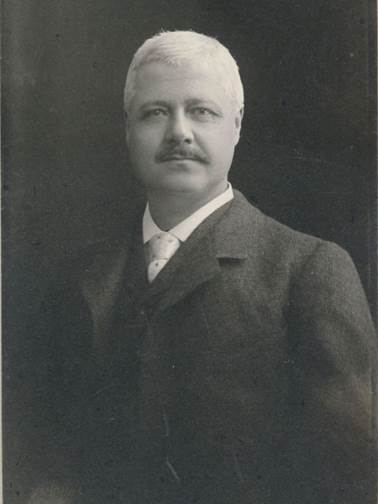

The museum

was founded in 1893. Its collection then consisted for a large part of donated

objects that scientists, travelers, and colonial traders brought to Switzerland.

A significant part of the original collection was provided as a donation by

Paul and Fritz Sarasin, two Swiss scientists and travelers based in Basel (MKB

n.d. b). The donation included numerous objects taken under asymmetrical power

relations from Ceylon during their research trips in the period of 1883-1925 in

the context of British occupation of the island (Schär

2015; Willi 2019, 4). Although some of the objects were reserved for

people with specific positions in spiritual rituals and others

were human remains meant to be buried, they were shown in numerous exhibitions

of the MKB and used as inspiration for racialized representations of “the

other” (MKB 2020), which is very problematic.

Figure 2 Fritz Sarasin

Figure 3 Paul Sarasin

In the

1970s, after Sri Lanka obtained political independence from the UK, the

director of the National Museum of Sri Lanka, Pilippu

Hewa Don Hemasiri de Silva,

filed a catalogue of objects violently taken from Ceylon that were scattered

over 27 countries (de Silva 1975). For those he considered to have important

cultural meaning for Sri Lanka, he filed a restitution claim to the responsible

UN office. The catalogue addressed objects scattered all around Europe and was

the very first request for restitution that reached Europe in an

institutionalized setting and thus with a force that made it impossible to

overlook. On that list were eleven objects that the MKB claimed as their

property. Suddenly, Switzerland was urged to take a stance in the question of

restitution and the handling of sensitive and/or stolen objects (Willi 2019,

4).

Figure 4 Files, random image

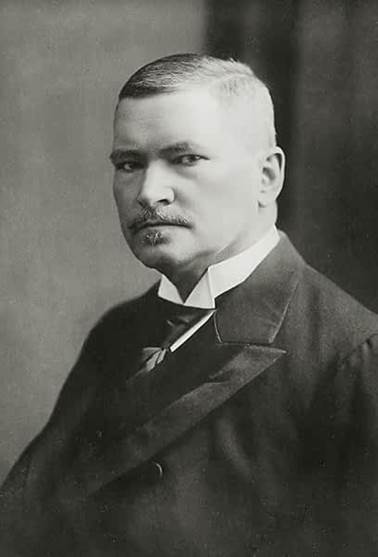

As all the objects that Sri Lanka

claimed back from Switzerland are in the hands of the MKB, its president at the

time Gerhard Baer played a major role in shaping Switzerland's extremely

cautious attitude towards restitution claims. For him the issue of collections

from formerly colonized areas was less an issue of colonial entanglements, reparations and forms of collaboration for the future, than

an image problem for the MKB and Switzerland that had to be dealt with (Willi

2019, 13). As a result, the reclaimed items were not returned

and the topic was dismissed and disappeared from the agenda of European

decision-makers.

Figure 5 Gerhard Baer

After many

years of hard work by people from formerly colonized countries an international

discussion on the handling of European colonial collections (re)emerged.

Important moments were the decision of the French president Macron to commit to

the restitution of cultural objects taken from West-Africa (Savoy 2018) and the

report of Savoy and Sarr proposing solutions for

European institutions (Sarr and Savoy 2018).

Figure 6 Benedicte

Savoy and Felwine Sarr

The MKB too

engaged in a critical reflection of its own collection with a special

exhibition named Thirst for Knowledge meets Collecting Mania in 2019-20 and has

given back single objects. Currently it is taking part in the Swiss Benin

Initiative which is a collaboration between Swiss and Nigerian institutions on

provenance research and transparency on collections from the kingdom of Benin. The

history of Paul and Fritz Sarasin and the objects they brought was researched

by the historian Bernhard Schär and taken up in a

play and art exhibition at the Theater Basel in 2020, engaging with a wider

public to disentangle Switzerland’s colonial relations (Ryser and Schonfeldt

2020).

Figure 7 Exhibition Thirst for Knowledge

meets Collecting Mania at the MKB 2019-2020

Exhibitions

like this can be a basis for an acknowledgement of the Museums and Basel’s

colonial entanglements that shape the city until today. And starting from

there, a basis for further research, practical missions as acquisition

policies, revision of narratives, policies on staff recruitment or educational

programs as well as restitution and a reorganization of collaboration between

institutions of the global North and South.

de Silva, P. (1975). A Catalogue of Antiquities and Other

Cultural Objects from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) Abroad. Colombo:

National Museums of Sri Lanka.

MKB (2020). Wissensdrang trifft Sammelwut. Ausstellungskatalog. Basel:

MKB.

MKB (n.d).

About Us. Seeing the World with Different Eyes. https://www.mkb.ch/en/museum/ueber-uns.html

MKB (n.d)

History of the Museum. https://www.mkb.ch/en/museum/ueber- uns/geschichte.html

Ryser, V. and

Schonfeldt, S. (2020), “Voices from

an archived silence. A Research and Exhibition Project

on Basel’s Colonial History. http://www.veraryser.ch/10/Stimmen%20aus%20einer%20archivierten%20Stille_Publikation.pdf

Sarr, F. , Savoy, B. (2018). Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine

culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle. N°2018-26. Paris: Ministère de la Culture.

Savoy, B. (2018). Die Zukunft des Kulturbesitzes.

FAZ.net. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/kunst-und-architektur/macron-fordert-endgueltige-

restitutionen-des-afrikanisches-erbes-an-afrika-15388474.html

Schär, B.

(2015). Tropenliebe. Schweizer

Naturforscher und niederländischer Imperialismus in Südostasien um 1900.

Frankfurt: Campus Verlag GmbH.

Willi, D. (2019). Tropendiebe? Die Debatte um die Restitution

sri-lankischer Kulturgüter im Museum für Völkerkunde Basel 1976-1984. Zürich:

Universität Zürich.