The Botanical Garden Basel and its Colonial

Heritage

Spalengraben 8 4051 Basel

Text

by Pina Haas

Botanical Gardens and questions

of de-colonizing ecology

Figure 1 The Botanical Garden. Photo S. Bryner, 11.02.2022.

Reading the

history of the botanical garden of Basel through a framework of de-colonial

ecology can serve to understand the deep entanglement of botany and botanical

gardens with the history and present of colonialism. The driving factor of this

entangled relationship is a fascination with the so-called ‘tropical’ and

‘exotic’. While contributing to education about and appreciation for other

species, biodiversity and nature conservation efforts, botanical gardens

worldwide have to be read in their historical context,

especially for their role in the colonial processes of Western appropriation

and ‘othering’ of the colonized peoples and lands and in the production of

hegemonic knowledge systems.

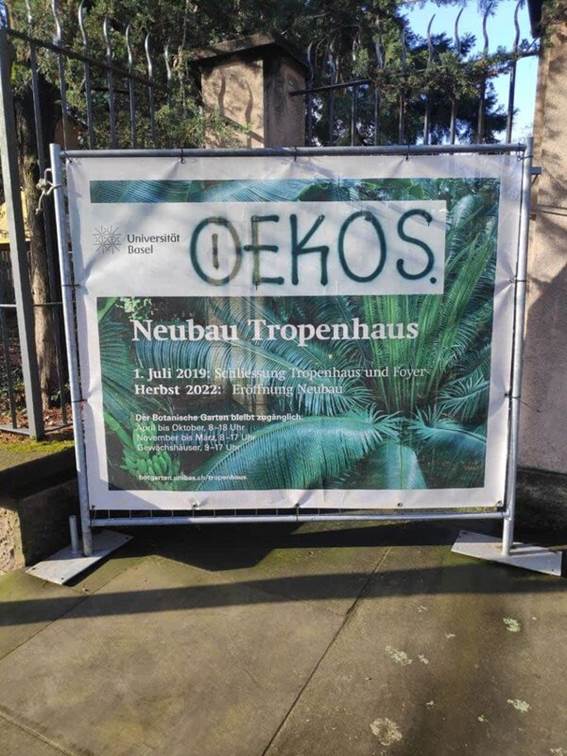

Figure 2 The new tropical building. Photo taken by

Saskia Bryner on February 11th 2022

Founded in 1589

by Caspar Bauhin - a botanist and anatomist at the

University of Basel - the botanical garden of Basel is among the oldest

worldwide. Up until the end of the 19th century, the botanical

garden of Basel was a small university initiative located at the Rheinsprung in Basel (Binz 1983).

Although the keeping of gardens in academic and scientific contexts existed for

centuries before, Johnson points out that “it is not until Europe expands its

exploration overseas and develops an empire that modern botanical gardens are

born and the idea of bringing together the flora of the earth in a single space

is inaugurated” (Johnson 2011, 103). This historical development is also

visible in the Botanical Garden in Basel. In 1895 the garden was relocated to

the current location at Spalengraben, a move which

enabled the enlargement of the garden’s collections and the construction of new

greenhouses (Binz 1938). During this time, the garden

was increasingly concerned with collecting and studying ‘exotic’ and ‘tropical’

plants and became an increasingly popular attraction for the public in Basel

and an expression of the fascination with the ‘other’ which was ‘discovered’ in

the colonization of the ‘New World’ (Schär 2015,

96-97).

Figure 3 Plants from abroad. Photo S. Bryner,

11.02.2022.

Even though

Switzerland did not have colonies as a nation itself, the country and

especially cities like Basel were very much involved in the process of

colonization and commercially and ideologically influenced by it. Swiss culture

was of course also influenced greatly by the European worldview that formed in

the wake of the enlightenment period and the spread of the idea of Western

superiority integral to colonialism (Schär 2015,

chapter 1). In terms of botany, Mastnak T., et al.

(2014) write that colonialism can be read as a “huge planting and displanting enterprise” (p. 364) which entailed the literal

and metaphoric “planting in” (p. 366) of people, plants

and animals at the expense of the “uprooting of indigenous plants as well as

indigenous people” (p. 365). The colonial plantation can be regarded as the

epitome of this “botanic colonization” (p 364). This pervasive domination of

people, fauna and flora is based on an assumption of

being in a rightful position to shape and rule over entire ecosystems which can

be argued to find its roots in Western modernity and persist up until today (Pattberg 2007). Botanical gardens are institutions in which

the colonial idea of such “government of nature” (Mastnak

et al. 2014, 367) is manifested. Plants are collected overseas and in botanical

gardens they are cultivated, protected, managed, and turned into a commodity

but in the colonies, these plants have been uprooted and wiped out to make

space for plantations and European landscaping (Mastnak,

Elyachar, and Boellstorff

2014; Heyden and Zeller 2007).

Figure 4 The Victoria House from the front with the

University Library building behind. Photo P. Haas, 15.07.2021.

The heart and

centerpiece of the botanical garden in Basel is certainly the Victoria House. The Victoria House (see figure 1) is specifically constructed for the

cultivation and showcasing of the large lotuses mostly referred to by the Latin

name Victoria Regia (Schmid 1996).

Considering the story of the lotus from a de-colonial perspective highlights

certain problems revolving around the Victoria

House. First, the plant (which the house was named after) was ‘discovered’

by Robert Schomburgk in an Amazon region in what is

today Guyana right after the country had become the first and only British

Colony in South America (‘Discovering

the Victoria Regia Water Lily', Pt. I 2013). The British botanist John Lindley then ‘identified’ the plant and named

it Victoria Regia after Victoria, the

queen of England at the time (Yeomans 2014).

Today Queen Victoria is associated with the era of industrialization and

the colonial expansion of the British Empire during the 19th

century. She is the first queen to carry the additional title “Empress of

India” (‘Victoria (r. 1837-1901)’ n.d.). Since then, the plant has become what Holway calls “the flower of Empire” and can be considered

an epitome of tropical fascination (Holway 2013). It

is important to remember that European scientists like Schomburgk

- although being promoted as such - “[...] did not discover nature in the

strict sense of the term, but only a reality already pre-interpreted and

pre-cultivated." What was reported about these foreign places, "was

therefore in essential parts a kind of transformation of the local prevailing

worldview into a European worldview” (Schär 2015,

14). Through naming plants, animals and even landscapes after Europeans,

natural scientists are glorifying personalities like Queen Victoria and

position themselves as discoverers of hitherto supposedly unknown species.

Figure 5 Inside the Victoria House in the botanical

garden Basel. Photo P. Haas, 15.07.2021.

What is forgotten

or obscured in this process of symbolic appropriation is the multi-layered

cultural and environmental history of these captivated and showcased species. Additionally to the Latin name Victoria, the lotus has been given multiple names with indigenous,

Spanish and folklore backgrounds (González 2007, 12). Irupé

for example is the name it is referred to by the Guarani, an indigenous people

living mainly in what is today called Paraguay. For them, the plant has great

cultural, cosmetic, and medicinal value and there is at least one important

mythical legend surrounding the lotus (González 2007; Martín 2014, 151-152).

For an

institution as central and proudly presented by the city and university as the

botanical garden of Basel, it would be important to critically engage with the

historical contexts of the plants exhibited and to recognize their various

cultural and religious meanings and local values for the indigenous communities

living in the areas where these plants were ‘discovered’. Situating the plant

in its complex and multi-layered background of meaning and history of

appropriation should be done to serve the de-naturalization of the European

naming and framing of plants and thus highlight the historic complicity of the

natural sciences in the dissemination of colonialist thinking and acting. In

the last few years, demands for the restitution of cultural artefacts and art

pieces looted in the process of colonization have become louder (see e.g. Hunt 2019).

Understanding botanical gardens like museal institutions as suggested by

Gramlich und Kray (Gramlich

and Kray n.d.) for example, demands a discussion about the questions of how

plants and species should be represented, how the institutions colonial

heritage can be adequately addressed and finally if and how plants and animal

species should and could be returned to their home regions.

References

Binz, A. (1983). Aus Basels botanischem Garten - Basler Jahrbuch 1938. Basel : Christoph

Merian Stiftung. Aus

Basels botanischem Garten - Basler Jahrbuch 1938 (baslerstadtbuch.ch)

González, J. E.

(2007). Hojas de sol en la victoria regia: La

razón de ser de un título. Hojas de sol en la victoria regia: Emergencias

de un pensamiento ambiental

alternativo en América latina. Universidad Nacional - IDEA Grupo de Pensamiento

Ambiental. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/12049/anapatricianoguera.2007_Parte1.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

Gramlich, N., Kray, L. (n.d)

Koloniale Geschichten des botanischen Gartens in Potsdam (Teil 1)’. Postcolonial Potsdam (blog). http://postcolonialpotsdam.org/2020/03/05/botanischer-garten-1/.

Heyden, U. van der.,

Zeller, J. ( 2007). Kolonialismus

Hierzulande: Eine Spurensuche in Deutschland. Erfurt: Sutton.

Holway, T.M. (2013). The Flower of Empire: An Amazonian Water

Lily, the Quest to Make It Bloom, and the World It Created. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Hunt, T. (2019).

Should Museums Return Their Colonial Artefacts? The Guardian: The Observer https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/jun/29/should-museums-return-their-colonial-artefacts

Johnson, N, C.

(2011). Botanical Gardens and Zoos. The SAGE Handbook of Geographical Knowledge,

edited by John A. Agnew and David N. Livingstone, 99–107. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Martín, P.

(2014). Pachamama Tales: Folklore from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay,

Peru, and Uruguay. World Folklore Series.

Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Mastnak, T. , Elyachar, J., Boellstorff, T. ( 2014). Botanical Decolonization:

Rethinking Native Plants. Environment and

Planning D: Society and Space 32 (2), 363–80. https://doi.org/10.1068/d13006p.

Oxford Academic

(2013). Discovering the Victoria Regia

Water Lily, Pt. I. Youtube Video. Oxford Academic (Oxford University Press). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koyzSQyn3u4.

Pattberg, P. (2007).

Conquest, Domination and Control: Europe’s Mastery of Nature in Historic

Perspective. Journal of Political Ecology

14 (1). https://doi.org/10.2458/v14i1.21681.

Royal UK (n.d). Victoria (r. 1837-1901). Royal UK (blog). https://www.royal.uk/queen-victoria.

Schär, B. (2015). Tropenliebe: Schweizer Naturforscher und

niederländischer Imperialismus in Südostasien um 1900. Campus Verlag.

Schmid, M. (1996). Ein königliches Haus

für eine Seerose Das Victoria-Haus als Bauform des 19. Jahrhunderts. Basler Stadtbuch 1996. Basel : Christoph

Merian Stiftung. Ein

königliches Haus für eine Seerose - Basler Stadtbuch 1996

Universität Basel. (n.d).

Geschichte | Botanischer Garten. https://botgarten.unibas.ch/de/garten/geschichte/.

Yeomans, J.

(2014). Victoria Amazonica - Inspiring a Nation |

Kew. Institution Roya. https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/victoria-amazonica-inspiring-a-nation.