Zoo Basel

Binningerstrasse 40, 4054 Basel

By Salome Rohner

Zoo Basel

Figure 1 A child watching a gorilla. Photo S. Rohner

11.2.2022

The Basel Zoo, known locally as the "Zolli", is the oldest

zoological garden in Switzerland and was opened in 1874 with the aim of

introducing the urban dwellers to the flora and fauna of their homeland. In the

late 19th century zoos were founded in many European cities. The

classification and systematization of nature is very typical for modernity, a

cultural complex that evolves in Europe after the “era of enlightenment” and

that is closely intertwined with the history of colonization. The construction

and hegemonization of a rationalized worldview by imperial forces finds a perfect

expression in the zoo. This became a space of representation for the modern

view of nature, which also served as propaganda for the progressive

colonization of non-European countries.

Because visitors to the Basel Zoo wanted more exotic exhibits soon

after the opening, the zoo's focus shifted from alpine animals to foreign

species, which shared the public’s attention in the zoo with touring

exhibitions and circuses. Such ensembles, which traveled throughout Europe,

often consisted not only of animals, but were intended to show the

comprehensive "way of life" of another place and culture, and

therefore also included the people and their dwellings. These were staged

together with the animals to give visitors a complete impression of everyday

life in the place in question.

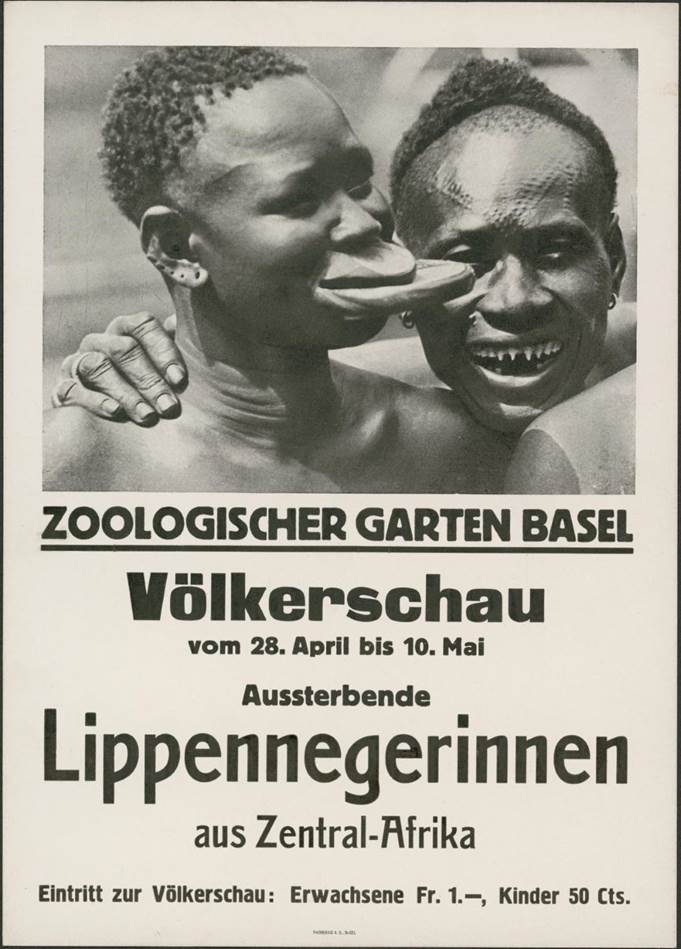

Figure 2 Poster

Völkerschau, 1932, State Archives Basel-Stadt.

The so-called “Völkerschauen” that were held on the meadow where today

the flamingos are housed, are one of the most problematic aspects of Zolli’s

past. Their history and conception are entangled with the origins of today’s

zoological gardens. Carl Hagenbeck, a tradesman for exotic animals and the

alleged inventor of the modern zoo started to exhibit people in his zoos and

circuses in the late 19th century. The Zoo Basel hosted 22

“Völkerschauen”, among them 3 were organized by Hagenbeck himself. For about 75

years these racist and exploitative exhibitions that also worked as propaganda

for the colonist activities by Europeans on other continents, were widely

accepted. For the “anthropological-zoological” attractions, people from all

over the world were transported to Europe, touring for months through the

countries, were paid very badly or not at all and were exposed to medical and

mental strains.

Hagenbeck’s heritage has contributed to the history of the zoo in many

ways. Even though “human zoos”, as they were called by the people, were

prohibited around the 1940ies in Switzerland, the depiction of western power

over “exotic animals” and non-European people that had been promoted by them

stays at the conceptual origin of the zoo. Hagenbeck’s vision of a “Zoological

Paradise” has influenced the presentation of animals in zoos all over the

world.

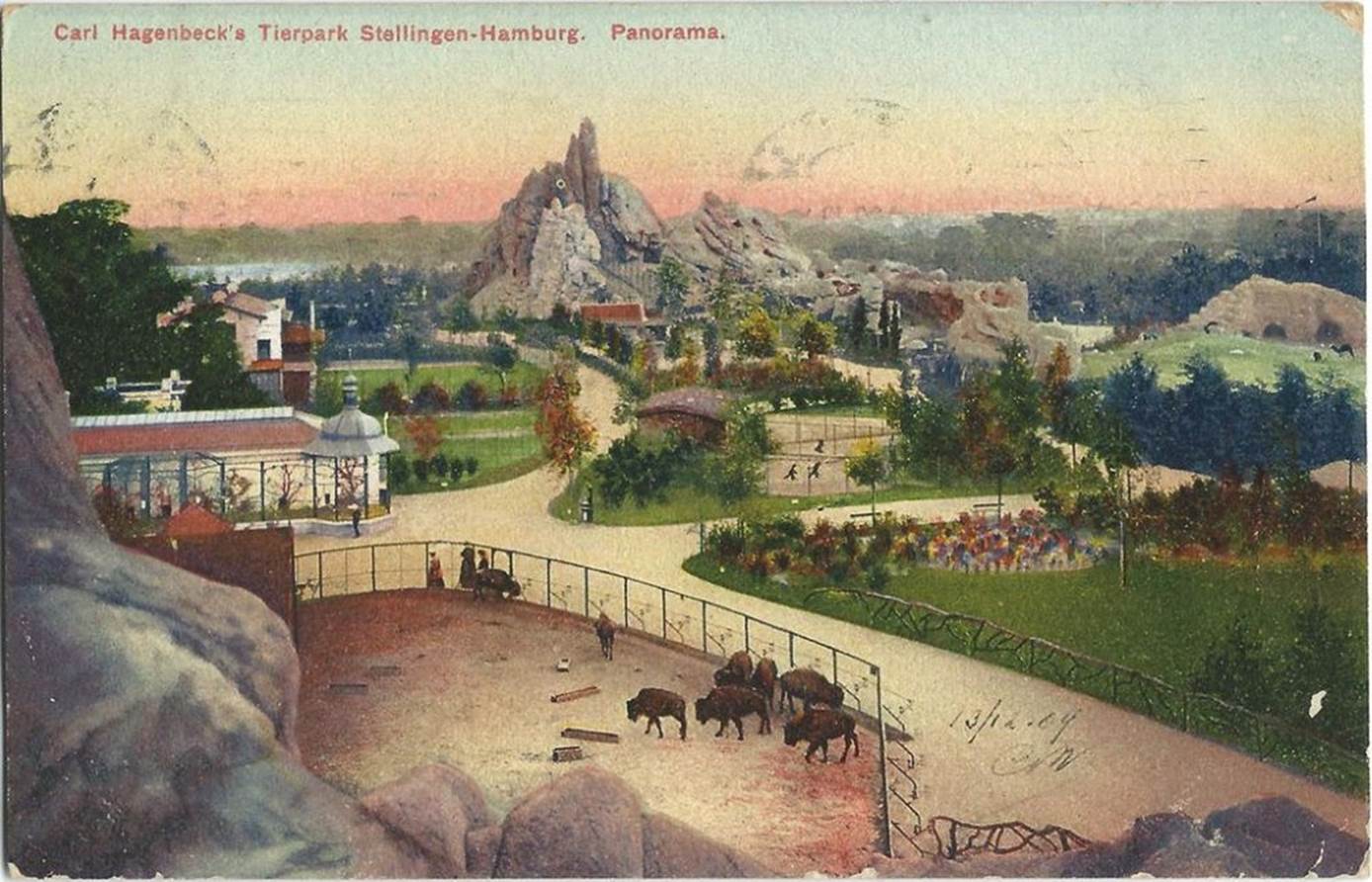

Figure 3 Postcard with Hagenbeck’s panorama in the

Hamburg Zoo, author unknown 1909, Creative Commons.

Instead of in a cage, the animals are staged in a built landscape

representing their “natural habitat”, creating a panorama within a

romanticized, artificial nature. Until today, in many zoos the architecture of

the enclosures imitates the original surroundings of species and is sometimes

even completed with depictions of indigenous buildings. We suppose that such

exoticized representations of foreign cultures is reminiscent of the

”Völkerschau” and contributes to the practice of “othering”. The Zoo Basel

today pursues a different style of exhibition that tries to focus on the animal

and the regeneration and preservation of species. Apart from its prominent

position in the city both in a spatial and historical sense, the Zolli is a good starting point

to reflect on colonialism in Switzerland. With its ability to reflect

global orders and cultural relations, and its reach to a wide audience, it

could play an important role in the decolonization of Swiss society.

Figure 4 Giraffes in the zoo. Photo

S. Rohner 4.2.2022.

References

Gregory,

D. (2004). The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq (Illustrated

ed.). WB.

Lutteroth,

J. (2013, April 12). a-56b4a247-0001-0001-0000-000000951096.

DER SPIEGEL, Hamburg, Germany. https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/tierpark-begruender-carl-hagenbeck-a-951096.html#fotostrecke-54351010-0001-0002-0000-000000110303

Rothfels,

N. (2002). Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo (Animals, History,

Culture). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Staehelin, B. (1993). Völkerschauen im

Zoologischen Garten Basel (1879–1935). Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Zoo Basel. (n.d.). Völkerschauen im. Retrieved 20 January 2022,

from https://www.zoobasel.ch/de/aktuelles/blog/3/zoo-geschichte/160/voelkerschauen-im-zoo-basel/